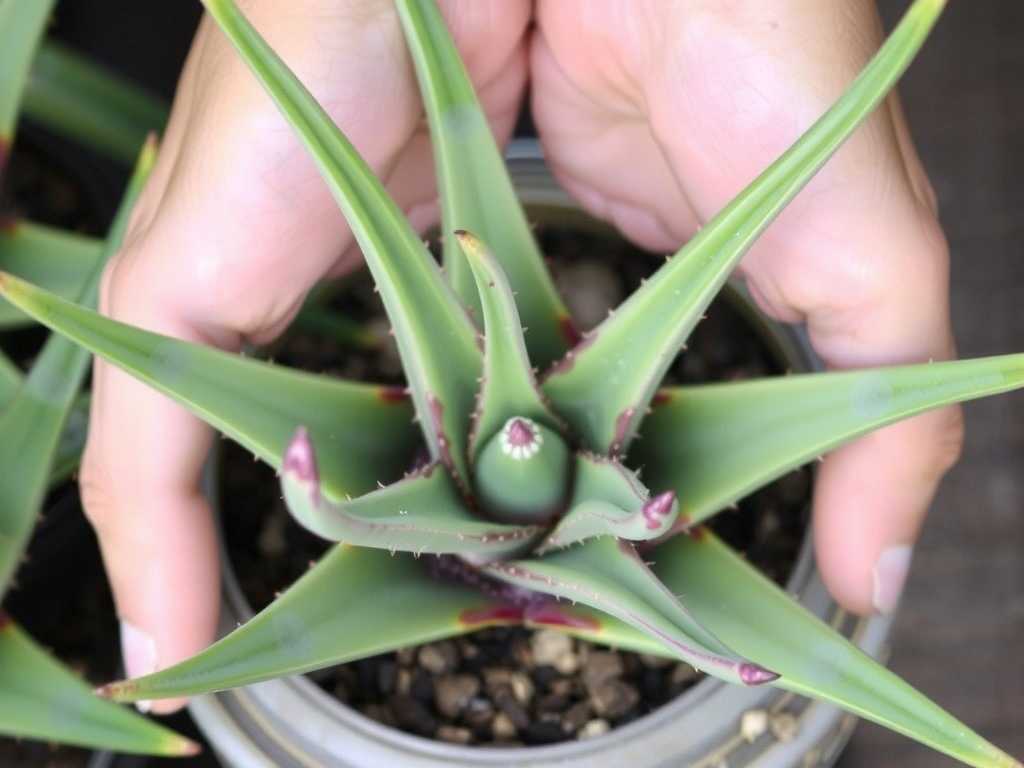

Aloe VeraLeaf Structure: What Each Part Does

Have you ever sliced open a plumpAloe Veraleaf, wondering what makes this gel so incredibly soothing? You're not alone. Many plant enthusiasts and natural remedy users see the leaf as a simple, gel-filled capsule. However, its internal structure is a marvel of natural engineering, specifically designed for survival and healing. Understanding theAloe Veraleaf structure is key to unlocking its full potential, ensuring you harvest the gel correctly, and appreciating why this plant is so much more than just a source of cooling gel. By delving into its anatomy, you'll learn exactly which parts to use, which to avoid, and how each layer contributes to its renowned benefits.

The Outer Protective Layer: The Rind

The first part you encounter is the tough, green outer skin, known as the rind. This isn't just a simple wrapper; it's the plant's primary defense system.

Imagine the rind as the plant's suit of armor. Its primary job is to protect the precious inner gel from the harsh external environment. It shields the plant from excessive sunlight, pests, and physical damage. The green color comes from chlorophyll, which allows the aloe plant to perform photosynthesis, converting sunlight into energy. The rind is also remarkably water-resistant, preventing excessive moisture loss in arid climates, which is essential for a succulent native to dry regions.

While the rind does contain some beneficial compounds, it is not typically consumed. It has a bitter taste and contains aloin, a yellowish-brown latex that can be a strong laxative and may cause stomach discomfort for some individuals. For most home uses, the rind is carefully removed to access the pure gel inside.

The Vascular Bundles: The Plant's Plumbing System

Just beneath the rind, running between it and the gel, lies a network of vascular bundles. These are the plant's circulatory system, and they play a crucial, yet often misunderstood, role.

Think of the vascular bundles as the aloe's intricate plumbing. They are responsible for transporting fluids, nutrients, and the products of photosynthesis throughout the plant. Xylem cells within these bundles carry water and minerals from the roots up to the leaf, while phloem cells transport sugars produced in the leaf to other parts of the plant. This system ensures the entire plant receives the nourishment it needs to grow.

This is also where you find the yellow sap, or latex, which is rich in aloin. When you cut a leaf, this sap can seep out. For topical gel harvesting, it's important to let this sap drain away, as it can cause skin irritation for some people. Its potent laxative properties are why it was historically used in certain medications, but it is not recommended for casual internal use without professional guidance.

The Mesophyll: The Treasure Trove of Gel

Once you move past the rind and the vascular layer, you reach the heart of the aloe leaf: the mesophyll. This is the colorless parenchyma tissue that makes up the bulk of the leaf's interior and is the source of the famous aloe vera gel.

The primary function of the mesophyll is water and nutrient storage. The cells in this region are specially designed to swell and hold vast amounts of water, which is why the leaf feels so thick and juicy. This stored water allows the aloe plant to survive long periods of drought. But it's not just storing water; it's storing a complex cocktail of biologically active compounds.

This clear, viscous gel is composed of about 99% water. The remaining 1%, however, is incredibly potent. It contains over 75 potentially active constituents, including vitamins, minerals, enzymes, sugars, lignin, saponins, and salicylic acid. This unique composition is responsible for the gel's moisturizing, soothing, and cooling properties when applied to the skin. It's this part of the leaf structure that makes aloe vera so effective for soothing minor burns, hydrating dry skin, and promoting wound healing.

The specific functions of the inner leaf gel are directly tied to its chemical makeup. The polysaccharides, like acemannan, are known for their immune-modulating and moisturizing effects. Saponins have cleansing and antiseptic qualities, while salicylic acid offers anti-inflammatory and mild analgesic benefits. When you understand that this gel is a specialized water-storage tissue, its hydrating power makes perfect sense.

How to Safely Harvest and Use Each Part

Knowing the leaf structure empowers you to harvest and use aloe vera safely and effectively. Here is a simple, step-by-step guide.

First, select a mature, outer leaf from the plant. It should be thick, firm, and growing from the base. Using a clean, sharp knife, cut the leaf as close to the base as possible. Place the leaf upright in a glass or bowl for about 10-15 minutes. This allows the yellow latex (aloin) from the vascular bundles to drain out.

Next, lay the leaf flat on a cutting board. Carefully slice off the serrated edges and the top and bottom tips. Then, using a knife or your fingers, separate the green rind from the clear gel. You can slide the knife just under the rind to fillet the gel out. Once you have the pure gel, you can blend it into a smooth consistency for immediate use or storage.

The fresh gel can be applied directly to the skin to soothe sunburn, moisturize, or calm irritation. For internal use, ensure you have thoroughly removed all traces of the yellow latex and rind, and only consume pure gel in moderation. Always consult with a healthcare provider before ingesting aloe vera, especially if you are pregnant, nursing, or on medication.

Is the yellow liquid in aloe vera dangerous?The yellow latex, found in the vascular bundles just under the rind, contains aloin. While it has documented laxative effects, it can cause stomach cramps and is not recommended for regular consumption. For topical use, it's best to rinse it off as it may cause skin irritation for sensitive individuals.

Can you eat the green skin of the aloe leaf?The green rind is tough, bitter, and contains aloin. It is not typically eaten. While some commercial processes may use it in filtered products, for home use, it is always best to peel it away and only consume the pure inner gel after proper preparation.

Why is my aloe vera gel watery and not thick?This is often a sign of an unhealthy plant or improper harvesting. A mature, well-watered (but not overwatered) aloe plant grown in plenty of sunlight will produce thick, mucilaginous gel. If the leaf's mesophyll tissue is watery, the plant may be stressed, too young, or overwatered, diluting the concentration of beneficial compounds.

From its protective rind to its intricate vascular system and its water-laden gel core, every component of the aloe vera leaf has a distinct purpose. This complex structure is precisely what allows the plant to thrive in harsh conditions and provides us with its multifaceted healing properties. By appreciating this intricate design, you can move beyond simply using aloe vera to truly understanding it, ensuring you harness its benefits safely and effectively for your skin and overall well-being.

发表评论